Originally written in Aug 17, 2022. Original work in Mandarin: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/ewrgbucoDvAmo3F4F_yYRA

Recently, I retrieved the CD and stereo, playing Haydn Variations performed by Zoltán Kocsis and Dezső Ránki at home. I adjusted the speakers on both sides of the table to the piano’s volume, closed my eyes, and lay on the table, as if Zoli and Dezi were really sitting on both sides of me playing the piano.

Part I: Brahms and A Variation on a Theme by Haydn

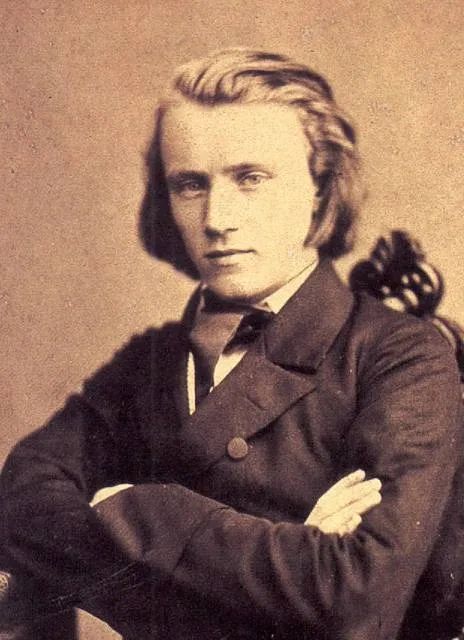

In 1856, the young Brahms wrote in a letter to his friend (and rival) Joseph Joachim, “Sometimes I contemplate the form of variations, and I always find that it needs to adhere more strictly and purely to the fundamental structure. The ancients consistently presented the theme in the bass. In Beethoven’s music, there are excellent variations in melody, harmony, and rhythm. But I must admit that sometimes newcomers (both of us!) become too engrossed in the theme itself (I’m not sure how to express this correctly). We grip the melody tightly, without giving it new treatment, let alone creating something new from it. We merely obscure it until the melody itself can no longer be discerned.”

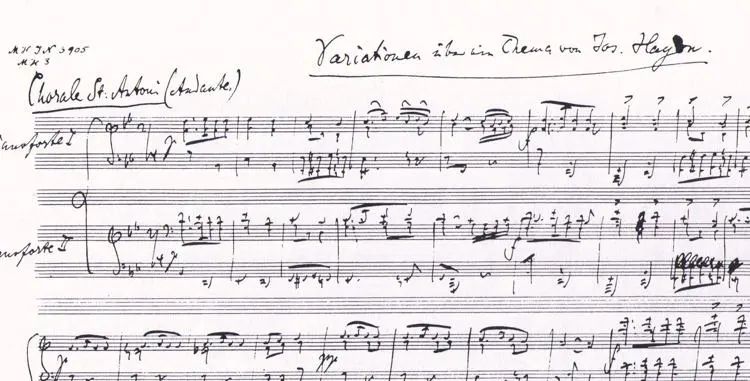

By 1870, Carl Ferdinand Pohl, who was working on a biography of Haydn, showed Brahms a recently discovered woodwind octet score belonging to Haydn. Brahms transcribed the second movement, the “Chorale St. Anthoni”, which became the theme for the “Haydn Variations.” In fact, it is still unknown whether the St. Anthony Chorale truly originated from Haydn. Publishers at the time often attributed works of lesser-known composers to more famous ones to boost sales. Some scholars believe the score of the second movement came from Haydn’s student Ignaz Pleyel. Additionally, because the melody itself was called a chorale, it is highly likely that it came from an existing church chorale.

Brahms completed the piano version of the variations (Op.56b) in the summer of 1873 in the Bavarian town of Tutzing, and immediately orchestrated it (Op.56a). The piano version was premiered in Bonn in August of the same year by Brahms and Clara Schumann, while the orchestral version was premiered in Vienna by the Vienna Philharmonic in November. The variations consist of a theme, eight variations, and a finale.

Based on the existing initial draft of the piano version, Brahms seems to have written the structure and details of the composition with clarity, without many preliminary sketches. Indeed, Brahms seemed to have moved past his initial anxieties, as evident in a letter he wrote to Sohubring 13 years after the letter mentioned earlier: “In a variation theme, the bass is truly important to me. The bass, to me, is sacred; it is the solid foundation upon which I construct the story. My treatment of other melodies is merely a game, a playful one… Once I have the bass, I can create and develop new melodies; only then can I create.”

The initial chorale is a Lutheran hymn, and the woodwind instrumentation reflects pastoral scenery. Initially, Brahms used the woodwind octet for outdoor performances. This pastoral atmosphere permeates the entire composition; Brahms enjoyed long walks in the countryside, and the melody of the variations might have evoked his hiking days in Tutzing. The eight variations are evenly divided into two groups. The first group creates tension through changes in major and minor keys and rhythms, while the second group primarily uses rhythm, not key changes, to achieve musical effects. Brahms indeed played a game, filling his variations with different elements: sudden loud and soft contrasts from Gypsy music (V. I), imitating hunting horns (V. VI), and styles used by composers like Berlioz and Mendelssohn to portray supernatural beings (V. VIII). Due to the difference in media, most of the more intricate rhythms in the piano score are shortened or omitted in the string score, and piano arpeggios are omitted altogether. However, the rich instruments of the strings provide the composer with more room to maneuver.

I personally prefer the piano version, especially the part at the end of the finale where the theme returns. Brahms added a choral-style melody to the theme, and the piano’s running arpeggios added an extra layer of energy, building up until the final repetition of the theme in chords. Even though the piano lacks the thickness of the orchestral arrangement to some extent, it possesses a bright clarity that the orchestra does not have, especially when restating the theme with octave chords—the penetration is unparalleled.

Part II: Zoltán Kocsis and Dezső Ránki

I’d like to briefly talk about the performers mentioned earlier, Zoltán Kocsis and Dezső Ránki. I translated a eulogy written for Kocsis last time but didn’t go into detail about him. Both were born in the early 1950s in Budapest. They first met because they were in the same grade at school. Later, they studied together with Pál Kadosa and finally at the Liszt Academy with György Kurtág, András Schiff, and others. They, along with another student of Pál Kadosa, András Schiff, were known as the Hungarian Trio. They toured Europe, received praise from Parisian newspapers, toured the United States, had their experiences turned into a documentary, and performed Bartók at Pál Kadosa’s birthday party.

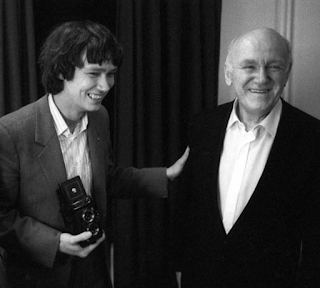

Later, Kocsis met Richter and received high praise from him. They performed Schubert’s piano duo together. According to Kocsis’ recollection, he was supposed to enjoy Polini and Richter’s performance, but Polini had a car accident, and Kocsis became a last-minute replacement (he always regretted not bringing formal clothes and had to perform in a white pullover). He urgently performed Schubert with Richter and later did three or four more shows together.

On January 14, 1985, in Budapest, Kocsis and Richter had a conversation in the dressing room of the Hungarian State Opera House. The 71-year-old Richter performed works by Haydn, Szymanowski, and Debussy with violinist Yuri Bashmet during the concert.

Although Ránki and Kocsis shared the same musical lineage, they had significantly different playing styles. According to Kocsis, due to their distinct styles, they could only find opportunities to perform together occasionally. After graduation, Kocsis chose to stay at the Liszt Academy to teach, while Ránki toured across Europe. In 1983, Kocsis and Iván Fischer founded the Budapest Festival Orchestra (which he carried around as a mascot during symphony concerts in the early years of the orchestra). Later, Kocsis also began conducting. He and Ránki reunited every couple of years to perform something.

A few days ago, I was watching the 2016 collaboration between Wang Yujia and Kocsis. Some people said that the smile and interaction between Kocsis and Wang Yujia during the curtain call reminded them of a young Kocsis and Ránki playing table tennis, laughing when they missed a ball. I always feel that this sensation is similar to what Brahms evokes in me. Concerts take people back to specific moments in time, and Brahms takes me back to Budapest, the Liszt Academy, the mutual gaze between Ránki and Kocsis during their performances, just like how there is always a shadow of the theme in each variation. The essence of the performance itself is preserved through recordings, memories, and the deep love for music.

Leave a comment