Originally written in Jan 9, 2022. Original work in Mandarin: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/yWS8EtUy0kILNe1BI44Qfg

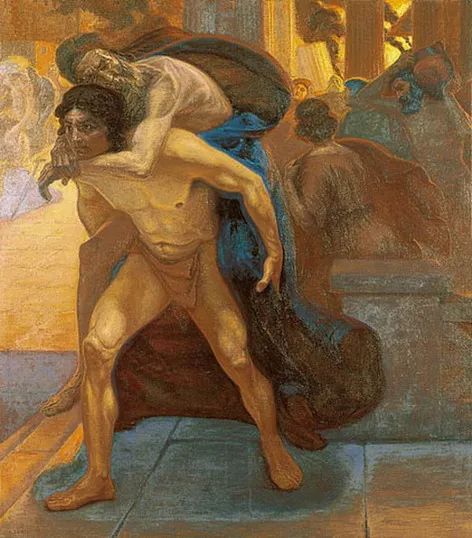

The Death of Dido

After the Trojan War, Odysseus struggled at sea to find his way back home. Meanwhile, Aeneas, the former commander of Troy, managed to escape the fallen city. He, along with others who fled, embarked on a challenging sea journey. They aimed to fulfill a great prophecy (at least in the eyes of the Romans): to find the legendary Italy and establish Rome.

In his search for Italy, Aeneas drifted to Carthage, where he met Queen Dido, who had also labored to build the city. The two fall in love, and Aeneas lingers. Until one day, the gods realize that their renewed serial has been out of order for a long time, and the messenger Mercury is sent by Jupiter to remind Aeneas. The latter came to his senses and left Carthage. This breaks Dido’s heart, and she orders Aeneas’ belongings to be piled up on a woodpile for cremation. The following day, she climbed the woodpile and ended her life on it.

Book 4: 659-673

So said she (Dido), with her lips pressed to the marriage-chair, “We shall die in vain.

But let us go to our death,” she said. “As it is, I would so go to the shades1.

Let the cold Trojan eyes, that drink this fury at sea.

And let Aeneas for ever bear the omen of our death.”

She finished, and in the midst of all this2

Her countrymen witnessed her fall on her sword, the

sword raw with blood-foam, and her hand splattered with blood. A roar resounded through the

High House: the god of rumor3, with her drinking and reveling nonsense, spread through the crumbling city.

Mourning, lamentation, and the cries of women in pain

reverberated through the town, and the deafening mournful cries echoed high in the air

Not dissimilar to this scene was the whole of

Carthage, or ancient Tyre4 was sacked by the enemy’s army

And the flames of wrath rolled above the crowd and the gods.

–

Dixit, et os impressa toro “Moriemur inultae,

sed moriamur” ait. “Sic, sic iuvat ire sub umbras.

Hauriat hunc oculis ignem crudelis ab alto

Dardanus, et nostrae secum ferat omina mortis.”

Dixerat, atque illam media inter talia ferro

conlapsam aspiciunt comites, ensemque cruore

spumantem sparsasque manus. It clamor ad alta

atria: concussam bacchatur Fama per urbem.

Lamentis gemituque et femineo ululatu

tecta fremunt, resonat magnis plangoribus aether,

non aliter quam si immissis ruat hostibus omnis

Karthago aut antiqua Tyros, flammaeque furentes

culmina perque hominum volvantur perque deorum.

Karthāgō aut antīqua Tyros, flammaeque furentēs

culmina perque hominum volvantur perque deōrum

audiit exanimis trepidōque exterrita cursū

In the 6th line, Virgil chooses to shift the perspective, describing Dido’s moment of death from the viewpoint of an onlooker. Because everything happens too suddenly, the actual process is too swift to describe and has already occurred. Similarly, Virgil chooses to emphasize the tragedy of Dido’s death by depicting a series of consequences triggered by her suicide. The metaphor in the last two lines implies the war between Rome and Carthage around a thousand years later.

Book 4: 687-690

She (Dido) attempted to open her heavy eyelids once more,

But she failed; the pierced wound beneath her chest

Screamed in agony.

Three times, she tried to sit up, propping herself up with her elbow,

Three times, she fell back onto the couch, her dazed eyes

Searching for the light in the depths of the sky, and then she moaned in pain.

–

Illa gravis oculōs cōnāta attollere rūrsus

dēficit; īnfīxum strīdit sub pectore vulnus.

Ter sēsē attollēns cubitōque adnixa levāvit,

ter revolūta torō est oculīsque errantibus altō

quaesīvit caelō lūcem ingemuitque repertā.

Book 4: 700-705

So Iris5, with the morning dew as her saffron wings,

Followed by thousands of different hues, with her back to the sun,

Descended from the sky and stood beside her. “I am commanded

to deliver this sacred lock of hair to Dis, and to release your soul from your body.”6

Having spoken, she cut the hair with her right hand, and at that moment,

all warmth retreated; Dido’s life dissipated into the wind.

–

Ergō Īris croceīs per caelum rōscida pennīs

mīlle trahēns variōs adversō sōle colōrēs

dēvolat et suprā caput astitit. “Hunc ego Dītī

sacrum iussa ferō tēque istō corpore solvō.”

Sīc ait et dextrā crīnem secat: omnis et ūnā

dīlāpsus calor atque in ventōs vīta recessit

- “Under the shades” refers to the underworld. ↩︎

- “These” could refer to the pile of wood or to the words spoken by Dido before her death. ↩︎

- The god of rumors, Fama, depicted earlier as a goddess with wings under which every feather was an eye, and a tongue and ear. ↩︎

- Tyre, Dido’s homeland. In the 9th century BCE, colonists from Tyre founded Carthage. ↩︎

- Iris, symbol of the rainbow and messenger of the gods. ↩︎

- Dido’s death was not ordained by the Fates; her soul was trapped within her body. Iris delivered her hair to Dis, the ruler of the Underworld, so she could peacefully reach the realm of the dead. ↩︎

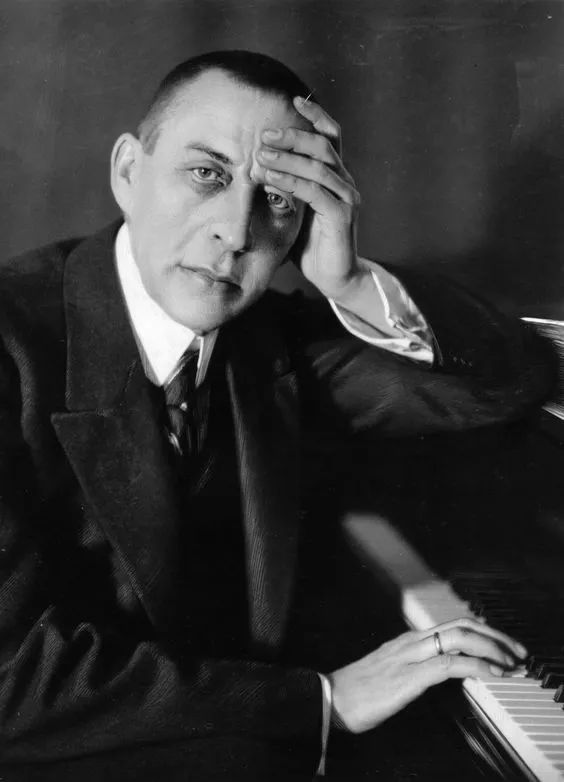

Rachmaninoff’s The Isle of the Dead

Rachmaninoff began composing this symphony in 1902. His friend, Alexander Siloti, included this unfinished work in Rachmaninoff’s concert program as early as 1903. In 1906, seeking solitude for composition, Rachmaninoff moved with his family from Moscow to Dresden. It was here that he completed the symphony. On February 11, 1907, in a letter to Nikita Morozov, he wrote, “A month ago, or maybe even earlier, I really wanted to finish this symphony, the draft of this symphony. I won’t announce it to the world until I’ve completed the final version.” He then complained about how exhausting it was to complete the piece. Upon learning this, Siloti urged him to premiere the symphony in St. Petersburg. This symphony is also the most popular among Rachmaninoff’s three symphonies.

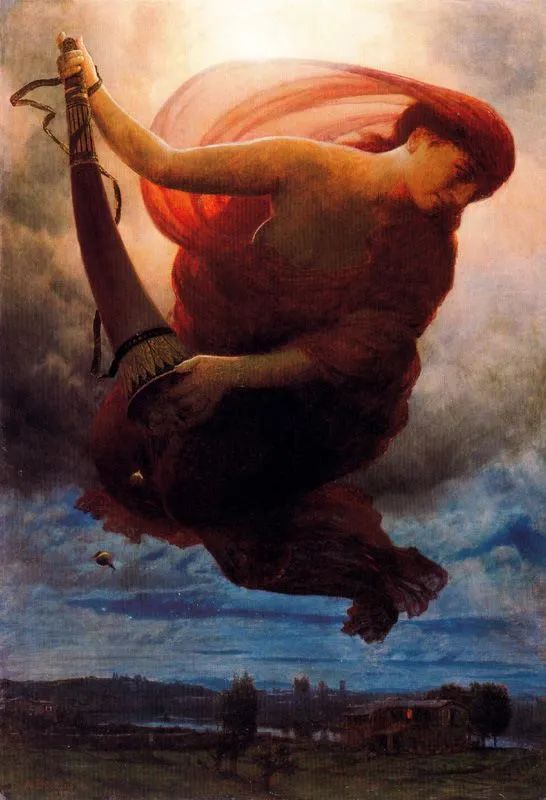

Although it first appeared in 1902, Rachmaninoff likely found true inspiration for it in 1907. He saw Arnold Böcklin’s painting Isle of the Dead in Paris, which was a black and white reproduction that sparked his creativity. Nikolai Struve suggested he use this painting as the theme for the symphonic poem. Later, Rachmaninoff saw different versions of the original colored artwork in Berlin and Leipzig (Böcklin painted a total of five versions of Isle of the Dead). Rachmaninoff himself said, “If I had seen the original first, I might not have written this symphonic poem.”

Although it first appeared in 1902, Rachmaninoff likely found true inspiration for it in 1907. He saw Arnold Böcklin’s painting Isle of the Dead in Paris, which was a black and white reproduction that sparked his creativity. Nikolai Struve suggested he use this painting as the theme for the symphonic poem. Later, Rachmaninoff saw different versions of the original colored artwork in Berlin and Leipzig (Böcklin painted a total of five versions of Isle of the Dead). Rachmaninoff himself said, “If I had seen the original first, I might not have written this symphonic poem.”

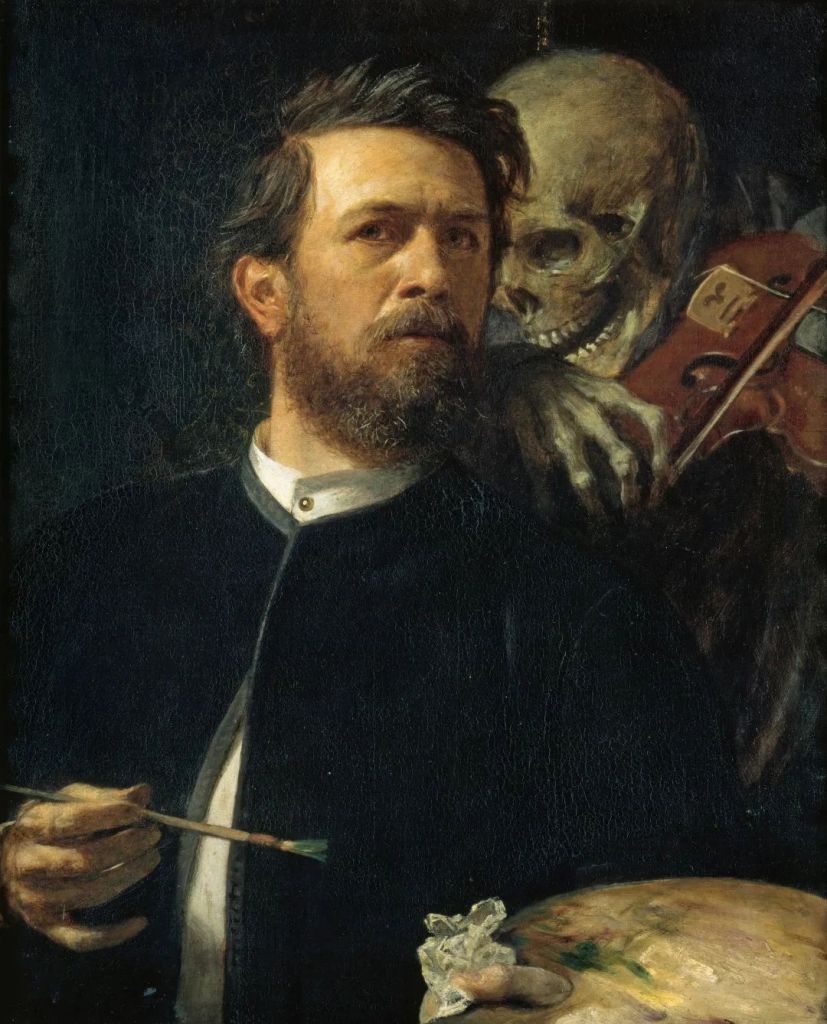

Interestingly, nearly all of Böcklin’s works were influenced by Nietzsche’s “spirit of music” (from Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy, the idea that music is an illusion of will, allowing people to confront the pain of life, though I might be wrong on this). Böcklin indeed understood the process of painting as akin to composing: “Just as two notes in music are harmonious, two colors are also harmonious; it’s only the intervention of a third party that can make them discordant” (not necessarily true). Some scholars believe Böcklin was a comprehensive aesthete. For instance, he depicted the sound of a bugle as crimson. Böcklin calculated with colors; his method of painting was a form of musical composition: he composed visual ideas and coordinated them with colors. In his paintings, the musical atmosphere was primarily created by the landscape, but this was often insufficient for him. Therefore, he would add characters playing other musical instruments.

A lot of Böcklin’s paintings feature the element of music

The motivation for the symphonic poem “Isle of the Dead” comes from the Dies Irae in the Requiem Mass. The melodic motif of three notes that runs throughout the entire symphony represents the sound of oars in the water as the dead are being transported to the island (a boat and oarsman appear in the painting). However, this symphonic poem is somewhat constrained by the overly repetitive rhythm.

Discussion

Virgil’s portrayal of Dido’s death, as well as the depiction of death in the two art forms, “Isle of the Dead,” presents death in a highly “enticing” manner. Dido’s death liberates her from suffering, while the Isle of the Dead portrays the calm and mystery of death. Whether it’s Dido’s unwavering acceptance of death, the oarsman’s silhouette in Böcklin’s painting, or the repetitive three-note motif in the symphonic poem, all confront death directly. We do not see fear in them; Dido hesitates not, the oarsman never looks back, and the sound of the oars continues.

The upper and lower pictures were painted in 1886 and 1883 respectively and are housed in Basel, Switzerland, and Berlin, Germany.

However, this calmness or magnificence does not imply a lack of attachment and love for life. Dido also attempted to open her eyes, symbolizing her realization that she couldn’t escape her fate. But Rachmaninoff’s symphony is definitive: the movements, shifting from calm to intense, transitioning from minor to major, equally depict a sense of struggle.

Citation

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/the-isle-of-the-dead-arnold-böcklin/0wFgMTIQ3kZCpg?hl=en

https://www.boosey.com/pages/cr/composer/timeline?composerid=2861

http://www.jstor.org/stable/25434456

http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/ncm.2008.31.3.245

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3384379

http://www.pianola.org/history/history_rachmaninoff.cfm

and Wikipedia, as always

Youtube: Patrick Yaggy

Aeneid, by P. Vergilius Maro

The Aeneid – A Translation into English Prose, by A. S. Kline

College Vergil, by Geoffrey Steadman

Rachmaninoff, by Michael Scott

Sergei Rachmaninoff – A Bio-Bibliography, by Robert E. Cunningham, Jr.

Semiotics of Classical Music – How Mozart, Brahms, and Wagner Talk to Us, by Eero Tarasi

Leave a comment